eRacks Systems Tech Blog

Open Source Experts Since 1999

USB 3.0 and SATA 3: Is It Worth It?

Two new high speed buses have recently become available to consumers, USB 3.0 and SATA 3. But are they worth considering now, or should you wait until they’ve been around for a while? Let’s first examine the differences between these interfaces and their predecessors, then take a look at the devices that are available and their associated costs and finally determine whether or not we should consider investing in them so soon.

What is USB 3.0?

USB 3.0 is the latest generation of the Universal Serial Bus standard, and was released in November 2008. USB has been in existence since 1994 and has been popular since 1998 with the release of the 1.1 revision, thanks to the true plug and play nature of the interface.

USB 2.0, the most common revision of the standard in use today, was released in April 2000, and supports a theoretical maximum data transfer rate of 480 Mbits/s, or 60MB/s. By contrast, USB 3.0, which was fully specified in November 2008, supports a theoretical raw maximum of 5 Gbits/s, or ~600MB/s, and is believed by the developers of the standard to be reasonably capable of sustaining 3.2Gbits/s, or ~400MB/s. Thus, USB 3.0 is roughly 10 times as fast as its predecessor.

Devices supporting USB 3.0 have been available to consumers since January 2010.

What is SATA 3?

Similarly, SATA 3 is the successor to the highly successful SATA 2 standard. Short for Serial Advanced Technology Attachment, SATA has been around since 2003. Both SATA 1 and SATA 2 were widely adopted and quickly grew popular, superceding the archaic IDE interface.

The final revision of the SATA 3 standard, released in May 2009, supports a theoretical maximum raw throughput of 6Gbits/s (in practice, peak throughput reaches ~600MB/s), twice the bandwidth of SATA 2 at 3Gbits/s, which itself is twice the bandwidth of SATA 1 at 1.5Gbits/s.

Devices supporting SATA 3 have been available to consumers since June 2010.

Is It Worth It?

First, let’s consider USB 3.0. Currently, there are a few USB thumb drives and external hard drives available that take advantage of the new standard. Unlike USB 2.0, which only supports a maximum of 60MB/s, USB 3.0 is capable of sustaining the highest data transfer rates hard drives can offer and more. USB 3.0 thumb drives are significantly more expensive than their USB 2.0 counterparts, but the external hard drives aren’t that much more expensive (the price difference between a USB 2.0 and a USB 3.0 external 1TB hard drive is only $10-$20), and given that two USB 3.0 ports will only cost you somewhere around $50, it might be worth upgrading if you have a need to access external storage quickly.

Now, what about SATA 3? Right now, you can purchase a Western Digital 1TB SATA2 drive for about $70.00. Conversely, a Western Digital SATA 3 disk of equal capacity will cost you about $95.00. The price difference between these two is only $25.00, so it’s not that much more expensive if you decide you’d like to double your bandwidth.

Keep in mind that if you’re using a 1x PCI-E SATA 3 controller, you won’t get the full 6Gb/s, but only ~4Gb/s. This is a limitation of the 1x PCI-E slot. With this in mind, if you’re not going to use an onboard SATA 3 controller, you’ll want to get a 4x card.

What eRacks Can Do for You

eRacks prides itself in staying up to date with the latest technologies. We currently offer on our high end models, upon request, support for both USB 3.0 and SATA 3, and can also build custom systems. Visit the eRacks website and place an order or request a quote today!

james September 7th, 2010

Posted In: Uncategorized

Living in a Land of High Capacity Storage

The history of computing is littered with examples of storage capacity overstepping software’s ability to effectively make use of it (for a list of examples — and an entertaining read — check out this old article from 2000: http://www.dewassoc.com/kbase/hard_drives/hard_drive_size_barriers.htm). Today is certainly no exception. With RAID arrays in excess of 32 TB (one terrabyte is ~1000 gigabytes), one must be thorough in their research, lest they discover the hard way that the software configuration they wish to use supports only a small fraction of the available disk space. The information contained in this article was compiled in an attempt to aid others in making wise decisions when making use of high capacity storage.

There are two basic considerations one must take into account. The first is partitioning. The second is one’s choice of filesystem (which in turn is often determined at least in part by the operating system.)

Partitioning

One of the most fundamental logical units of storage, treated by most operating systems as a “disk” in its own right, is the partition. For those of us who are unaware of what a partition is or why it’s important (those who know might want to skip ahead to the next paragraph), imagine the North American continent. Though in reality it’s a single physical chunk of land, it’s separated into logical boundaries: Canada, the United States and Mexico. Without these boundaries to demarcate those areas of land available to each country, it would be much more difficult to decide which resources belong to whom. In the same vein, partitions exist to logically separate a hard disk into regions of storage designated for various purposes.

The problem here is that in the original BIOS-style scheme, one can only create partitions of up to 2 TB in size. This is because the BIOS-style partition table, which makes use of a 32-bit address space, can only keep track of up to 2^32 blocks, each typically 512 bytes in size. Multiplying these two quantities gives us the maximum 2 TB. There are two ways to approach this problem.

The first is to accept the limitation and to create many small partitions. The disadvantage, of course, is that you must spread your data out over a large area. The Logical Volume Manager (LVM) on Linux can somewhat mitigate this problem by tying everything together into a single logical disk, but even so, we can certainly do better.

The second, and in my opinion the superior choice, is to stop using traditional BIOS-style partitions and to instead make use of a relatively new standard known as GPT (GUID Partition Table). Unlike BIOS-style partition tables, a GPT uses 64-bit addresses, meaning that each partition has a maximum size of 2^64 blocks x 512-bytes per block = 8 ZB (that’s zettabytes; for comparison, 1 ZB = 1 billion TB). That’s A LOT better than 2 TB!

The tradeoff, if you choose to go the GPT route, is that not all operating systems support it. At the time of this writing, the following are known to NOT support GPT (or at least not without jumping through some hoops): FreeBSD (partial support for GPT partitions exists), OpenBSD, NetBSD (GPT filesystems are supported via dkwedges, but cannot be booted from directly), OpenSolaris (again, GPT is supported for separate data partitions, but cannot be booted from directly) Fedora Core, CentOS and RedHat Enterprise Linux and Windows XP or below (GPT only works in Windows XP x64, and only for separate data partitions). This is not an exhaustive list. By contrast, here is a list (also not exhaustive) of operating systems that do fully support GPT partitions out of the box: Debian, Ubuntu and Gentoo Linux, Windows Vista and Windows 7.

Your choice of operating system will therefore determine whether or not you can take advantage of what GPT has to offer.

Filesystem Considerations

Now that we’ve got the partitioning figured out, we’ll have to consider filesystem limitations. The rest of this article assumes that you’ve either made use of a GPT partition or that you’re on Linux and have created one large LVM volume.

You might be tempted to think, “now that I have a large partition, I just have to format it and I’m done!” Sometimes this is true, as is the case with any version of Windows that supports GPT partitions and *BSD (assuming you’ve jumped through the hoops necessary to create the partition in the first place.) If you plan to use Linux, however, you’ll need to be a little more careful, as you have a few choices available to you, not all of them supporting large volumes.

The default Linux filesystem for a long time was ext3. It does support large filesystems, but with a 4K block size, it will only address up to 16 TB of space. You can create an ext3 filesystem with an 8K block size, for a maximum size of 32 TB, but only if you’re working with an architecture that supports 8K page sizes (and unless you’re using an Itanium or an Alpha processor, you’re probably out of luck.)

More recently, ext3 has been superceded by ext4. Theoretically, ext4, with 4K blocks, supports up to 1 EB (exabyte, equal to 1 million TB). However, for now, due to limitations in the tools used to create ext4 filesystems, you’re still limited to 16 TB. Hopefully, this will be fixed in the not too distant future.

Fortunately, Linux does support filesystems that can span across large volumes. These include (but are not necessarily limited to) XFS (up to 16 EB) and JFS2 (up to 32 TB).

Conclusion

Eventually, these issues will be smoothed over, just like all the others that have surfaced throughout the history of computers. For now, however, one must take some time to plan how best to utilize large capacity volumes, as the software industry still has quite a bit of catching up to do.

eRacks Open Source Systems well understands the issues faced when dealing with so much storage, and will be more than happy to help you with your needs. Check us out at http://www.eracks.com, and call for a quote today!

Ikaria Lean Belly Juice reviews point out that this product is the best for weight loss. At last you will get the body you dreamed of so much. With just one click you can find out how to access it. Check it out and make yourself happy once and for all. What a wonderful product and one I will buy again.

I got 3 boxes for $12.50 each and the shipping was very speedy. They arrived promptly. The package was absolutely packed perfectly. You could take them outside and pick the kind you like. What a great change to a day spent training.

james August 4th, 2010

Posted In: Uncategorized

Open Source Media Center Solutions

I’ve been evaluating various open source media center applications in an effort to put together a new unit and had the opportunity to weight the relative pros and cons of each. Below, you’ll get to read about my findings and hopefully learn a little bit about what’s out there. So, without further ado, here’s a list of the packages I looked at, in order of preference.

1. Boxee

(http://www.boxee.tv/)

Boxee was my first pick. It has a slick interface, can draw from a variety of different sources such as Hulu and Youtube out of the box, makes available a plethora of plugins (called “applications”), is easy to navigate and has an interface very suited for a remote control. The biggest con for me is that, while the project itself is open source, in order to use it, you need to register for an account on their website.

2. XBMC

(http://www.xbmc.org/)

XBMC, which stands for “X-Box Media Center,” was originally designed for the X-Box and has since been made available on the PC. It sports a very polished interface, and like Boxee, is easy to navigate and makes using a remote control easy. Support for online sources such as Youtube is missing out of the box, but there are plenty of plugins to help. Unfortunately, unlike Boxee or Moovida (which is next in our list of applications), you have to go to external sources in order to find them (check out http://www.xbmczone.com/). Supposedly, it’s easy to install a plugin once you’ve downloaded it, but the directions I found online differed from how things worked with the latest version, and I ended up having to install plugins manually by unzipping them and copying the files to the right directory.

3. Moovida

(http://www.moovida.com/)

Moovida, formerly known as Elisa, is another media center option. Like Boxee and XBMC, it sports an easy to navigate interface suited to a remote control, and unlike XBMC, integrates the process of finding, installing and updating plugins a part of the application itself. The reason why I rated this one below XBMC is that there aren’t a lot of plugins available, and because the interface to XBMC is, in my opinion, slightly more polished.

4. Miro

(http://www.getmiro.com/)

(My reason for rating Miro at the bottom isn’t that Miro is a bad application. In fact, I enjoyed using it. It comes with support for many video feeds by default and does a good job of organizing media. My problem, for our purposes, is that it’s not such a great application for set top boxes. The UI is easy to use, but I don’t think it would be as friendly when hooked up to a TV with a remote control. Also, it’s difficult to add sources such as Youtube, as you have to manually add RSS feeds for the channels that interest you. Nevertheless, it’s a useful application, and I recommend giving it a try.

james August 6th, 2009

Posted In: media center, multimedia, Open Source

Tags: audio, media center, Open Source, video

The Folding@home Project

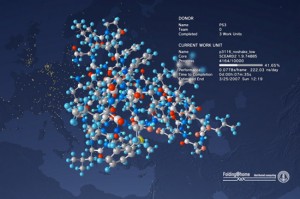

Do you have a server lying around someplace that spends a significant amount of time in idle? If so, you might want to consider running the Folding@home client. Folding@home is a project based at Stanford whose goal is to simulate and study protein folding, which is crucial in order to understand and develop better treatments for serious diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

An example of the Folding@home client on a Playstation 3

Folding@home has been one of the most successful examples of distributed computing, whereby individuals all over the world donate spare CPU cycles in order to perform calculations and send the results back to a central location. The project started back in October of 2000, and has since resulted in the publication of over 40 works, and has lead to significant progress in the fight against Alzheimer’s. To date, the Folding@home project has been and is being used to study Huntington’s Disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, among other serious medical conditions.

The Folding@home client runs on Windows, Mac OS-X, Playstation 3 and Linux, and will run in the background while your computer completes other tasks. If you want us to install it for you, just say so in the notes field of your order. In addition, if you wish to make a donation to the project, just specify “Donation Target: Other Open Source Project” and specify Folding@home in the notes field.

For more information about Folding@home, see http://folding.standford.edu/

james June 16th, 2009

Posted In: Research

Tags: donate, fold, folding@home, protein, stanford

eRacks Sony Laptop – Part 2 – Shrinking partitions & Installing Linux

eRacks Sony Laptop – Part 2 – Shrinking partitions & Installing Linux

Step 1 – back up Vista partitions

[joe@sony ~]$ sudo su

Password:

[root@sony joe]# fdisk /dev/sda

The number of cylinders for this disk is set to 14593.

There is nothing wrong with that, but this is larger than 1024,

and could in certain setups cause problems with:

1) software that runs at boot time (e.g., old versions of LILO)

2) booting and partitioning software from other OSs

(e.g., DOS FDISK, OS/2 FDISK)

Command (m for help): p

Disk /dev/sda: 120.0 GB, 120034123776 bytes

255 heads, 63 sectors/track, 14593 cylinders

Units = cylinders of 16065 * 512 = 8225280 bytes

Disk identifier: 0x200c5cbf

Device Boot Start End Blocks Id System

/dev/sda1 1 889 7138304 27 Unknown

Partition 1 does not end on cylinder boundary.

/dev/sda2 * 889 4076 25600000 7 HPFS/NTFS

/dev/sda3 4077 4101 200812+ 83 Linux

/dev/sda4 4102 14593 84276990 5 Extended

/dev/sda5 4102 14593 84276958+ 8e Linux LVM

Command (m for help): q

[root@sony joe]# dd if=/dev/sda2 | gzip -9 – >vista.img

51200000+0 records in

51200000+0 records out

26214400000 bytes (26 GB) copied, 2384.53 s, 11.0 MB/s

[root@sony joe]# ls -l

total 6168412

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Download

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Public

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Videos

-rw-r–r– 1 root root 6310241019 2009-02-20 21:58 vista.img

[root@sony joe]# dd if=/dev/sda1 | gzip -9 – >recovery.img

14276608+0 records in

14276608+0 records out

7309623296 bytes (7.3 GB) copied, 739.479 s, 9.9 MB/s

[root@sony joe]# ls -l

total 12022456

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Download

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Public

-rw-r–r– 1 root root 5988678705 2009-02-20 22:15 recovery.img

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Videos

-rw-r–r– 1 root root 6310241019 2009-02-20 21:58 vista.img

[root@sony joe]# mv vista.img vista.img.gz

[root@sony joe]# mv recovery.img recovery.img.gz

[root@sony joe]# ls -l

total 12022456

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Download

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Public

-rw-r–r– 1 root root 5988678705 2009-02-20 22:15 recovery.img.gz

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 joe joe 4096 2009-02-20 03:05 Videos

-rw-r–r– 1 root root 6310241019 2009-02-20 21:58 vista.img.gz

[root@sony joe]#

Step 2: Boot from the Ubuntu CD and install Linux!

Previous: Part 1 – the OOB Experience

eRacks Sony Laptop – Part 3 – Virtual Windoze

joe June 9th, 2009

Posted In: Laptop cookbooks, Open Source, Products, Technology

Tags: laptop, linux, Notebook, Open Source, Sony, Technology, ubuntu, Windows Tax